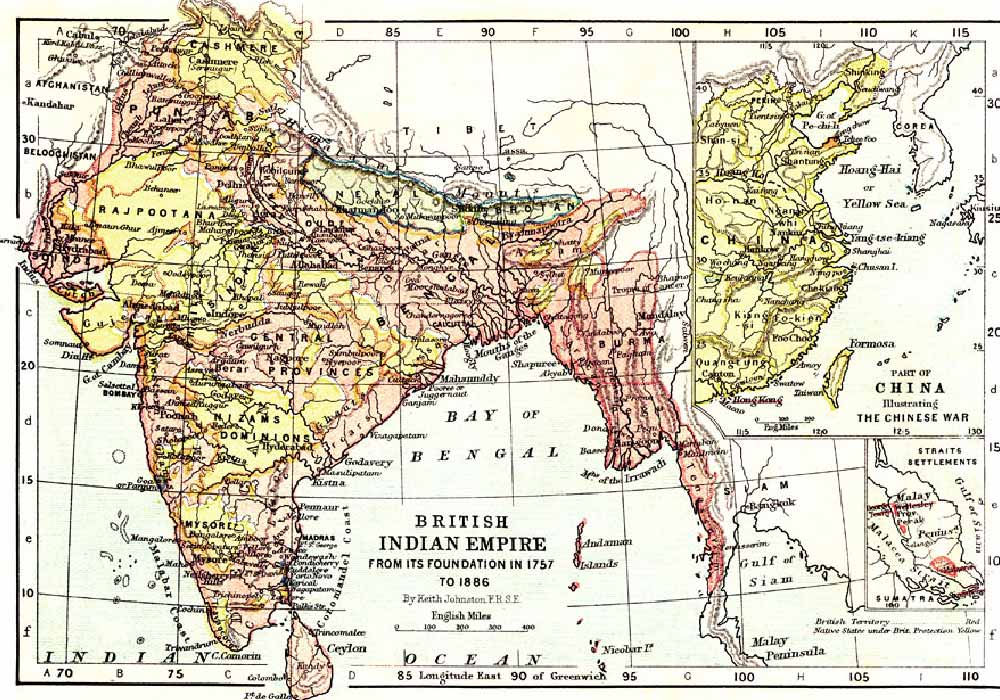

NZBMS was new on the scene, founded in 1885, and nobody had yet been sent overseas. Its focus was a special need of B—al which they had heard about from both British and Australian Baptists. NZBMS took this so seriously that they were seeking only women missionaries.

A Miss Fulton from Hanover Street Baptist Church in Dunedin volunteered and Rosalie Macgeorge from the same church, offered in August 1886 with the idea that the two should work together. Miss Fulton then pulled out but Rosalie stayed the course.

The Beginnings

Rosalie was born in Australia, the third of nine children, and probably came to NZ when she was about five. In her middle twenties, Rosalie was described as “A young woman of fine appearance, strong character, and deep devotion to her Lord.” She had been baptised 12 years before, had joined and was serving the church, and was an able speaker. She had grown up in the Hanover Street church with her family, who were respected and active members. She was a trained teacher, and had a special love for children — a love and understanding that was demonstrated later in the many letters she wrote to them from India.

Rosalie’s departure was a rush. She could travel with C—ta-bound English Baptist global workers Mr and Mrs Kerry. Her farewell was on 28th September, 1886, and she asked for the prayers of God’s people, especially as difficulties would confront her. The minister, Rev Alfred North, noted that the occasion was unique as Rosalie was the first global worker from the Baptist denomination in New Zealand to go overseas, and the first woman sent by any NZ group for global work. Then he said, and this proved very true, ‘the work which lies before you is exceptionally hard and exhausting.’ He mentioned disappointments, pity, compassion, hope deferred, ignorance, time-consuming language study, separation from loved ones and climate.

Rev North charged her,

…Go! In the assurance that His presence yields. Go! In simple faith in the power of the Gospel of His love. Go! Your heart over-brimming with love to all on whom His love is set, and for whom His blood was shed. So shall the blessing of the Lord Almighty, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, rest upon you for ever.’

Rosalie reached C—ta in December that year and travelled to F—r to study Bengali. She was impatient to start work but recognised she must do about two years of study.

There was bookish, classical Bengali as well as common spoken language. Once she got her words mixed and called her pundit not ’teacher’ but ‘cow’. He was not amused. But Rosalie was never content with the books. She insisted on gaining colloquial words, tones and twists of language, even asking local children to correct her. She wanted free conversation style, something many global workers had missed out on.

Settling in

By early 1888 she could write, ‘I feel I could do a little in the zenanas if necessary, but it would be blundering work, and would cripple me in the language for the future.’ She kept studying. She prepared a short talk she could give as her first one, carefully correcting the pronunciation. Her joy was great when seven weeks later, very uncertain, she found she was understood when she spoke to the women in a house. Yay! She was getting somewhere. She visited five houses a week and talked to the women for an hour.

A local pastor was preaching at a mela (festival) and an Australian young woman, Miss Newcombe, and Rosalie helped by giving out tracts and singing hymns and Rosalie added playing on her concertina, with which she was quite competent. Miss Newcombe told the story of Rosalie saving a little girl’s life. The girl was bitten on the leg by a snake, and her father saw Rosalie walking past and called her. ‘She ran and applied a ligature above the bite, and then sucked out the snake poison. Her quick resourcefulness undoubtedly saved the life of the child, who, within a few days was almost completely well again. The parents sent two sons to the Sunday School.’

N—unj

NZBMS wanted a site of their own from which to work. D—a was suggested, but Rosalie wanted somewhere smaller, so they chose the sizeable river port, N—unj. The Australians and Rosalie asked the committee in NZ to send them more workers as soon as possible. Rosalie’s sister Lillian offered to come, and soon Hopestill Pillow as well. Rosalie started by walking the streets of N—unj in local dress over her dress to indicate she wished to identify with the people. Initially she spoke to a few women who were willing to learn to read.

Some did not mind her Bible teaching but on occasion, some asked her, ‘Do you intend to teach that Jesus is the Son of God?’ When she said ‘Yes,’ they said point blank, ‘We don’t want you.’ The men grew noisy and vehement. But Rosalie quietly and bravely held her ground, said a Bengali hymn or gave out tracts, offered to come into the homes and talk to the women if they invited her. After, she asked to be allowed through the crowd and walked quietly away, followed by the children.

Soon she had invitation to visit 30 homes weekly where there were about three women in each. Some women listened happily. Some didn’t. Some babies cried too loud for lessons. Some women chattered non-stop. Some asked questions. ‘Why don’t you get married?’ ‘What soap do you use?’ ‘Will you have a smoke?’ ‘What did you eat for breakfast?’ ‘How much money does the government pay you?’ ‘How do you twist your hair up?’ ‘Let us see the colour of your feet.’ It was hard work, especially with the language difficulties, but some women were also interested in what Rosalie believed.

Children especially loved Rosalie and she loved them and taught them songs that helped them remember her lessons.

Difficulties

Miss Newcombe became unwell and in 1889 doctors told her to return to Australia and not return to South Asia. This was a big blow to Rosalie, who needed a fellow-worker and friend.

Rosalie’s health had been good but in April 1889 she was unwell and sent to the cool of the hills, to D—ling at 7000 feet, to take a break. In June she returned to N—unj feeling much better, but was promptly dragged down in health and by July was again unwell and feeling affected by the loneliness. Right then, while expecting her sister Lillian to set out for South Asia, Lillian was given a negative health report and told to stay in New Zealand.

Staying was becoming difficult. No land had been bought for the NZ base and no decision made. But N—unj itself added to Rosalie’s difficulties. Her biographer notes that ‘The sights and sounds appalled her, the smells, the poor hygiene, the lot of women, the plight of the widows, the sad little child-wives, the rudeness and discourtesy of the men, the poverty, the disease, and the godlessness of the English residents, the idolatry…She was never free of it and she had no one to share it with.’

Still, there were some good things. A woman who, in great discouragement, turned to Jesus for help and continued to pray. Another, at the end of Rosalie’s tiring day of visiting homes, who said she believed in Jesus Christ and her husband had concluded the Bible was a true book. Rosalie now had some new friends to nurture. Two men (able to write where most women could not) sent letters later, appreciating so much her kindness and proud to be younger brothers in Jesus.

Strategy and developments

During 1889 Rosalie worried the NZBMS committee back in NZ by refusing, after praying about it, to accept personal salary. They tried to dissuade her, fearing she may no longer heed their advice if not accepting pay. But she was determined. She believed God would bless a simple life of trust. She felt receiving a salary compromised people’s view of her, making them think she was a government agent. And she wanted to free up global funds to support others. So instead she lived with a local family, earning her keep by teaching English and other subjects, and immersing herself in local culture more.

At this time, NZBMS enlisted the help of Australia and British Baptists to try and settle on a place for an NZ base. With Rosalie’s encouragement, they chose B—ria (east of N—unj).

About this time Rosalie again became ill. She stayed in her hut and one evening a small boy peered in and saw her pray to her God. When she asked her house owner for some goat’s milk she carefully checked that the woman’s child would not receive less milk because of her. This little story had a surprising aftermath: many years later a man asked at a nearby Christian base to be baptised. The pastor asked how he came to be there. He said he was the small boy that Rosalie had been concerned about. His mother had then pledged not to decrease his milk, and he’d been deeply impressed by this, and the lady’s piety, unselfishness and gentleness. So years later he had searched for, and found, the Jesus whom Rosalie was praying to.

Two new companions and an experienced middle-aged couple arrived from New Zealand to work with Rosalie. Miss Hopestill Pillow, Miss Bacon, and Mr and Mrs Emeric de St Dalmas, who had joined NZBMS after experience in India within the British Baptists. Their new task, to run the site in B—ria work, was a comfort to Rosalie, who was thankful to have friends from home.

Final days

In January 1891, Rosalie wrote home that she was well and strong again and ready for another year’s work. However, at a routine doctor’s visit, she was told to return immediately to New Zealand. Reluctantly, she left East B—l to go home via Sri Lanka. Old friends the Carters met her in Ceylon, finding her ill with a fever, and immediately arranged a stay inland. Though attended by a skilled doctor she passed away six days later on 12 April 1891. She was 31.

Global workers and Tamil Christians sang as they carried her to her resting place in the garden town of Kandy. In four and half years she had, with faith and zeal, trailblazed cross-cultural work for the generations that would come after.

Adapted from https://www.bwnz.org.nz/womens-history-month-rosalie-macgeorge-1859–1891/

0 Comments